Supply Chain Frontiers issue #45

A key challenge in humanitarian and global health supply chains is product expiry. Shelf life begins the moment a product completes manufacture, and once it expires the product is considered unsuitable for use. Some distributors have found ways to manage the problem, but further research is needed on how expiry dates impact the supply of medicines.

Product expiration has major impacts. In these resource-limited settings, resulting financial losses represent resources and drugs not available to meet needs, and ultimately patients may not have access to treatment they desperately need. Most expiry and disposal occurs at the end of the supply chain, in country, where expiration is currently at unacceptable levels in every stage (WHO, 2010). Anecdotal evidence suggests expiry is also a significant issue in humanitarian supply chains. For example, long lead times during the 2004 tsunami response saw 6.5% of product expired on arrival and 67% within less than a year (Bero et al., 2010).

Shelf life varies across products and even dosage forms. While the shelf lives of many pharmaceuticals are between three to five years, vaccines often have 12 months or less, and laboratory supplies six to 24 months. Humanitarian organizations typically specify the remaining shelf life required at time of shipment from the manufacturer and to the country of use. Countries may have additional requirements; a rule of thumb for products used by public health systems in developing countries is that at least 60–80% of shelf life be remaining when product enters the country.

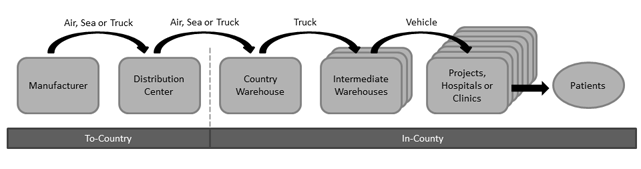

As shown below, in the typical supply chain, product flows from the manufacturer to a distribution center (DC) in Europe, the United States, or the region of use. For example, the international non-governmental organization (NGO) MSF ships most medicines through European DCs. On the other hand, US-based SCMS supplies HIV/AIDS medicines to 14 African countries from regional DCs in Africa. Once in country, product is typically stored at a central warehouse near the capital. Product then may flow through intermediate warehouses to reach points of use – project locations, health clinics, or hospitals.

Global Health Supply Chain

MSF Supply, one of MSF’s European-based distribution centers, manages shelf life by ordering shorter shelf-life items from manufacturers more often and asking country projects to order them more often. They use a First Expiry First Out (FEFO) policy when picking medicines to be shipped. For assembly of kits that contain many items, they use a Last Expiry Last Out (LELO) policy.

Ongoing evolution of health programs and treatment contributes to expiry. For large health programs, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, changes to country-level treatment protocols and drug selection are frequent and have a large impact on demand, making demand uncertain. Furthermore, when new programs and approaches are introduced, the timing of scale-up and uptake by doctors and patients may not be as anticipated. Lastly, high levels of emergency preparedness stock may be needed to be responsive, but then be subject to expiry.

A significant cause of expiry in the supply chain is oversupply resulting from the mismatch of supply and demand. This may occur in a big incident when program changes are not communicated. For example, if the changes to the treatment regimen for HIV/AIDS are not quickly and effectively communicated, unneeded product may be ordered and never used.

For expiry to be well managed in country, ordering and delivery must work throughout the entire public health system, which can include several intermediate warehouses and many points of use. In less developed countries, these systems are weak and fragmented. Functions to match supply and demand, such as forecasting, quantification, and procurement, may all be weak. An error in these functions can result in more product than can be consumed before its expiration, especially when long transport times and sporadic delivery compromise the shelf life of arriving product. The results are often handfuls of expired product at hundreds of health clinics and warehouses across the country.

A second cause of expiry in country is a lack of good warehouse management in terms of visibility to expiry and adherence to the FEFO pull policy. This is also a result of weak in-country systems, particularly human resources and information systems. Currently, expiry is managed through periodic reports created by hand detailing products that will expire in the next six months. However, this level of planning has been shown to be insufficient.

Thinking about this complex problem, there is an opportunity for academics to contribute through research into specific questions. What is the right level of expiry? How should expiry be measured? How much shelf life should be “allocated” to transit, to time spent at a distributor’s warehouse in Europe, and to in-country receipt, transport, stock, and use? How should shelf life be reflected in supply chain design decisions, such as order frequency for countries and transport mode? Lastly, how can public health system execution be strengthened?

This article was written by Natalie Privett and Laura Rock Kopczak, Zaragoza Logistics Center, Zaragoza, Spain. Two of Zaragoza Logistics Center’s current research projects touch on expiry. An EU-funded project examines supply chain visibility, and a project with MSF Supply investigates demand forecasting, including forecasting for short shelf-life products. For more information on the research described, contact the authors.

References: Bero, L.; Carson, B.; Moller, H.; and Hill, S., 2010. To give is better than to receive: Compliance with WHO guidelines for drug donations during 2000–2008. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, Issue 88, pp. 922–929.

WHO, 2010. Mapping of Partners’ Procurement and Supply Management Systems for Medical Products, Nigeria: Federal Ministries of Health.