What Is Vulnerability?

A firm's "vulnerability" to a disruptive event can be viewed as a combination of the likelihood of a disruption and its potential severity. Companies assess their vulnerabilities by answering three basic questions :

1. What can go wrong?

2. What is the likelihood of that happening?

3. What are the consequences if it does happen?

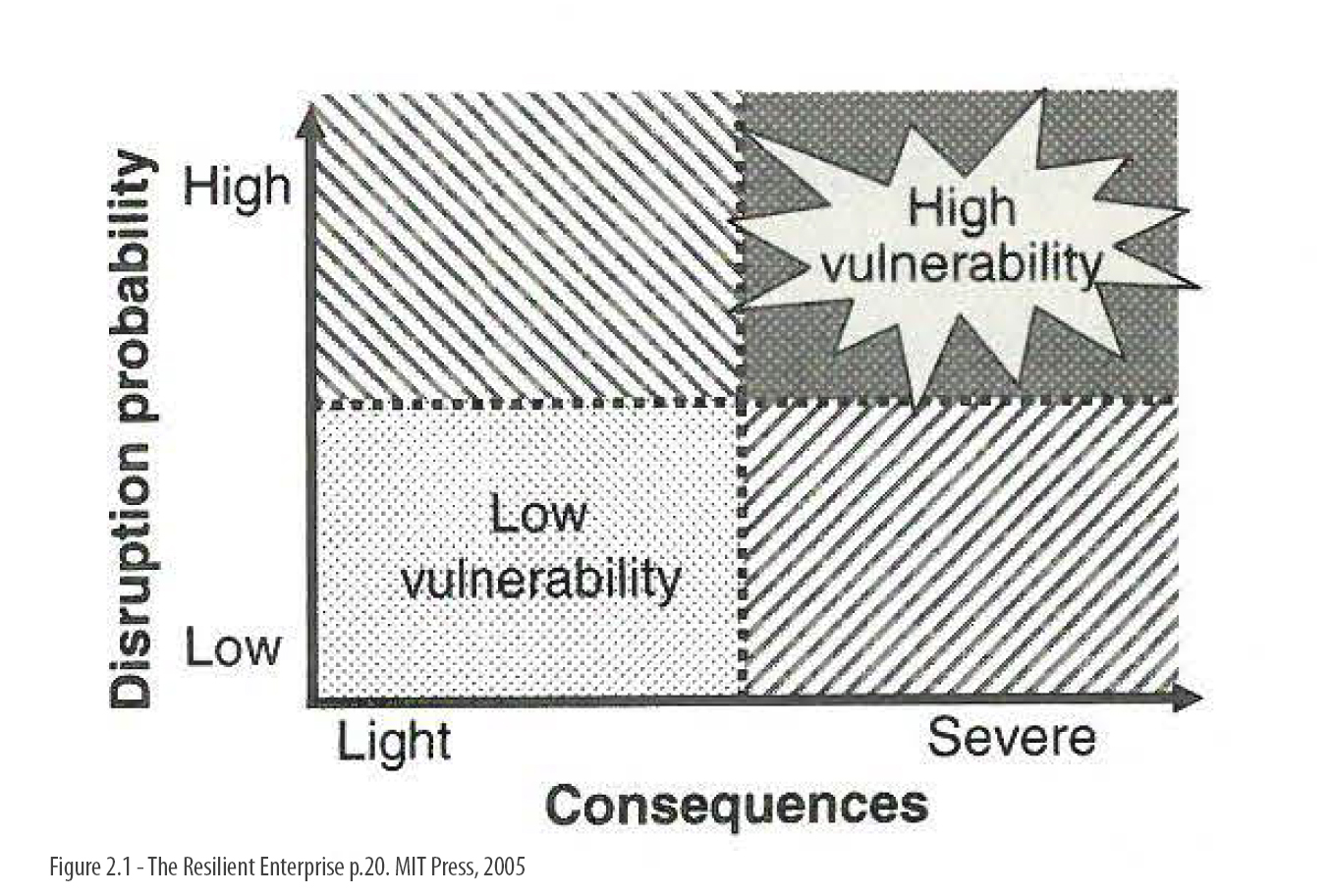

Figure 2.1 provides a way of thinking about the confluence of probability and consequences of events (the second and third questions above), such as an earthquake or a fire at a plant. The vertical axis is the probability of the disruptive event and the horizontal axis represents the magnitude of the consequences.

Figure 2.1, p.20, The Resilient Enterprise, MIT Press, 2005

Vulnerabilities are too varied and too nuanced, and the tools for measuring the factors are too blunt, to distill these factors easily into a single "expected vulnerability" metric. Such a metric would be the product of probability and consequences. Thus, each of the four quadrants of figure 2.1 has a specific meaning . Vulnerability is highest when both the likelihood and the impact are high. Similarly, rare low-consequence events represent the lowest levels of vulnerability.

But what might appear to be a set of modest vulnerabilities may have little in common for business planning purposes. These include disruptions that combine low probability and large consequences, on the one hand, and those characterized by high probability but low impact, on the other. High-probability/low-impact events are part of the scope' of daily management operations, tending to the relatively small random variations in demand, unexpected low productivity, quality problems, absenteeism, or other such relatively common events that are part of the "cost of doing business." Low-probability/high-impact events, on the other hand, call for planning and a response that is outside the realm of daily activity.

Prioritizing Vulnerabilities

Given their complexity, modern supply chains can be disrupted in many ways. Each individual link in the chain is not likely to suffer a particular rare event, but the chances are that the chain as a whole will be disrupted somehow. The challenge for managers is to understand and communicate this vulnerability to their colleagues and senior executives. Various graphic presentations can help managers visualize their company's vulnerability. Each provides a different view onto vulnerability in terms of how much, where, and to whom.

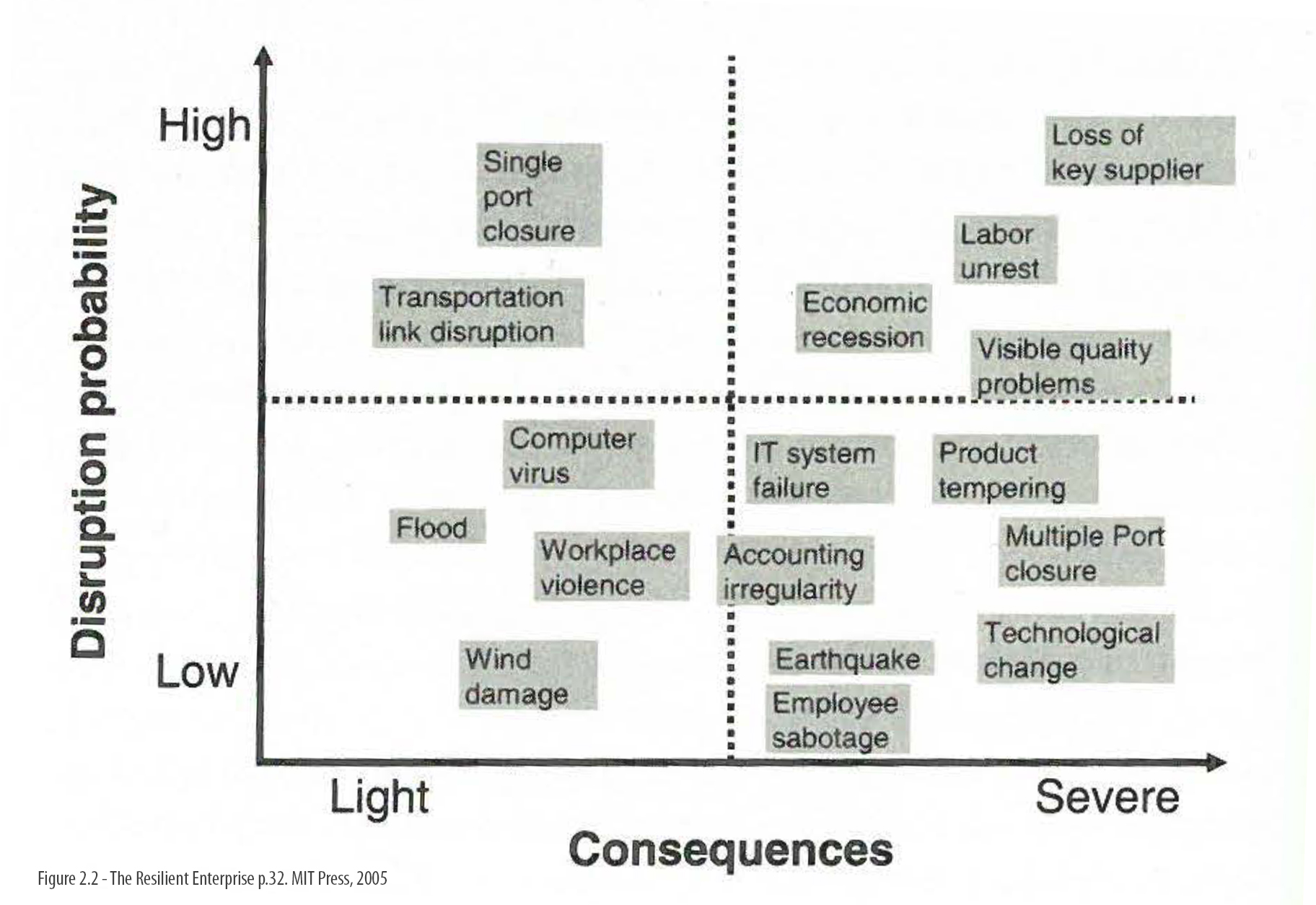

Figure 2.2 used a two-axis framework of likelihood vs. impact to compare the vulnerability of various companies to specific disruptions. Similar, yet differently focused, enterprise vulnerability maps be used to categorize and prioritize different possible disruptions for a given company. Although it may be quit e difficult for any enterprise to estimate accurately the likelihood and consequences of each disruption, such maps serve to highlight the relative vulnerability along these two dimensions , leading companies to focus on the disruptions to which they may be most vulnerable. Figure 2.4 depicts such a map for a hypothetical manufacturing enterprise.

Figure 2.2, p.32, The Resilient Enterprise, MIT Press, 2005

Multinational companies realize that many disruptions are tied to geography; floods, earthquakes, political upheaval, fluctuating exchange rates, and other potential causes of disruption are focused on certain geographical locations. GM is tracking geographic content of parts to help understand the total enterprise risk of disruptions in particular parts of the world. To this end, GM follows the bill of material, which is a list of all the parts and quantities used in the manufacturing of each product. Aggregating these data at the enterprise level help paint the total exposure of the enterprise to countries and regions. At a minimum, a geographic vulnerability simply depicts which suppliers of what parts are located in each area of the world. Such a map can focus the company's planning efforts on sensitive regions and help it spot a problem area at a glance and respond quickly. What most companies do not have is a complete vulnerability picture that includes their supplier vulnerabilities.

A more advanced version of the geographic vulnerability map focuses on the connectedness of the supply chain to help understand interdependencies. Such a supply chain map highlights the flow of parts out of given regions, depicting who is involved and the plants in other parts of the world that are dependent on them. Such a map can become a tool for understanding the extent to which a flood in Brazil will affect production in Singapore or sales in Germany.

GM uses such supply chain vulnerability maps to simulate the impact of disruptions and the efficacy of proposed mitigation efforts . The data for these simulation models are taken from the bill of material for all GM products . But the data also include process maps depicting the dependency between various processes across the enterprise.

GM's work on risk management offers benefits beyond dealing with disruption. Studying how the company is interconnected and how different processes affect each other helps the company improve day-to-day operations. "We've learned a lot about the enterprise as we've been working on this," Elkins says. In particular, supply chain mapping can lead to identification of redundant processes, opportunities for consolidations (for example, when several divisions are buying parts from the same supplier and can aggregate their volume to achieve better procurement terms), coordination of logistics activities across plants and divi- sions (for example, using back-and-forth trucking services rather than one way), and many others.

What Next Related to Prioritizing Vulnerability?

The three questions posed in this chapter regarding low probability/high-impact disruptions are:

1. What can go wrong?

2. What is the likelihood it will take place?

3. How severe will it be?

The operating consequence s of these questions are:

1. What should managers focus on?

2. What can be done to reduce the probability of a disruption? 3. What can be done to reduce the impact of a disruption?

There are two ways to look at what managers should focus on. The first is to list and prioritize events (such as earthquake, hurricane, strike, and sabotage) that can lead to disruptions. The second is to list disruptions (for example, reduced production capacity, shortage of a critical part, or a severed transportation link, and analyze their causes (and consequences). The first is more useful when thinking about reducing the probability of a disruption since the relevant actions involve treating the source of the problem. The second is more useful when considering how to recover from a disruption, since the cause may be less relevant than the consequences and their severity at that point.

What is particularly important to realize is that high-impact disruptions are not as rare as they appear . Only when focusing on a single type of disruption, like an earthquake at a particular place, are the chances low. Taken as a whole, however, it is likely that some kind of disruption will hit somewhere almost routinely at a firm that depends on a global, large, and complex supply chain. As a result companies should focus on supply chain designs, processes, and corporate cultures that are generally resilient, in addition to assessing the likelihood and the consequences of various disruptions, and investing in security.

Excerpt from: The Resilient Enterprise, MIT Press, 2005